Wednesday, 14 Oct 2020

Here we look at how test content is developed, tested and refined before it makes it into a trusted progressive achievement assessment.

The news is full of stories about medical trials which, until the COVID-19 pandemic struck, was an unlikely subject to be making headlines. Although the need for a vaccine is urgent, the process of careful testing – particularly in a situation in which lives are at stake – is vital in order to reduce risk and produce the best possible end result. Trialling is a significant part of the test development process too; although the stakes are admittedly lower, an equally rigorous process is applied to making sure that student assessments are reliable, valid and robust. So how does content make it into ACER's trusted progressive achievement assessments?

How is content developed?

ACER has designed and delivered countless assessments in its 90 years, in keeping with developments in assessment theory, methods of data gathering and analysis, and contemporary approaches to teaching and learning. In the process, we have developed an extensive pool of content (test items) that has been rigorously trialled to ensure it is valid, reliable and fit for purpose. Meanwhile, our expert team of test developers builds the content bank continuously, adding items that have been developed by panels of content specialists, proofread and reviewed for quality assurance purposes, in accordance with test development best practice.

How we trial content

Assessments often contain trial content mixed in with items already shown to be valid and reliable. We invite schools to take part in trials and, in this way, we are able to test the performance of content in a real-life setting to ensure it performs as expected, offering the right level of challenge to the students sitting the test and confirming it is appropriate to the assessment type and method of delivery.

Currently we are testing content for a new PAT Spelling (Foundation-Year 10) assessment and an exciting adaptive version of PAT Reading (Years 1-9). Schools play an invaluable role in helping us ensure that PAT continues to offer the best, most reliable student assessments available.

Validating that content is a complex psychometric process involving rotated cluster design, a representative sample of students and Rasch Measurement Theory. After trialling, the data is analysed by experienced psychometricians for fit, discrimination and difficulty, and selected for use in the final product. Rasch allows us to plot student ability and item difficulty on the same progression scale in order to ensure the assessment is targeted appropriately. By selecting items according to their position on the scale we are able to ensure that students are tested at a level that matches their ability in that subject area. In this way, assessments morph and change, and we effect continuous improvement.

Items that fail the test

Items that fail to meet the high standards required for inclusion in an ACER assessment, such as the following examples, are deleted from the pool.

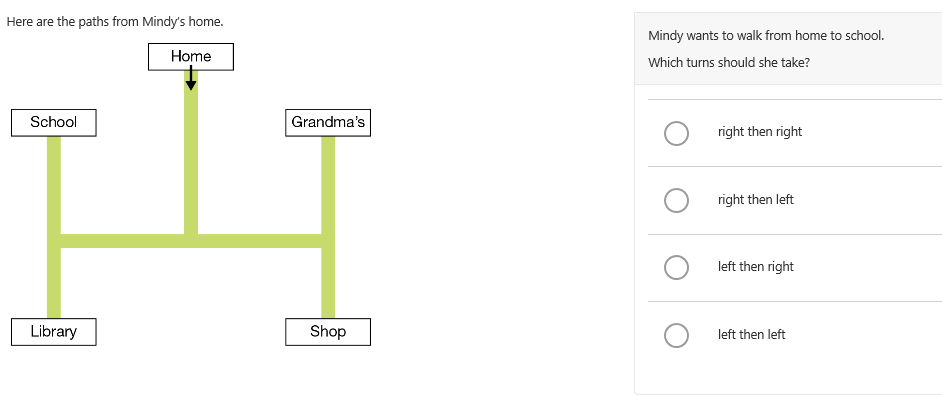

This question was designed for inclusion in PAT Maths and was tested with Year 1 students.

The trial data revealed that a disproportionate number of low-performing students got this question correct and vice versa for high-performing students, which suggests that many students were guessing. The data also seem to suggest that the item contained mathematics that did not fit with other questions in the test. It may be that, despite being in the Year 1 curriculum, students did not have enough experience with maps to be able to engage with a map that is oriented upside down. They may also have struggled to remember left and right.

More students of all ability levels chose option C than the correct option (A). This suggests that the difficulty was in interpreting the map. In order to better match the ability levels of Year 1 students and prevent guessing, the question could be changed so that the map had the same orientation as the person looking at it, with ‘Home’ at the bottom; then the first turn could be more easily determined. Or perhaps the cognitive load could be reduced by providing an even simpler map with only one possible turn. Furthermore, an example could be provided so that children are required to engage with the map before answering a question; for instance, ‘To walk from Home to Grandma’s, Mindy turns left then left’.

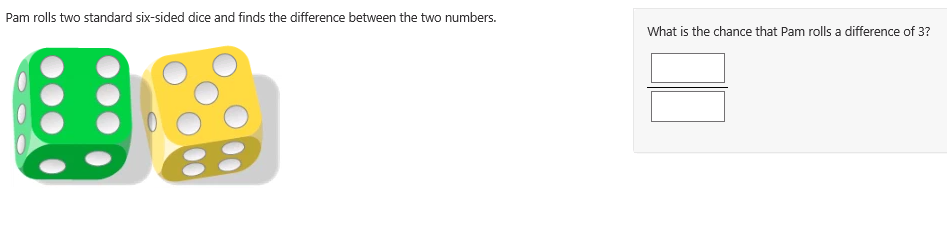

The following PAT Maths item was tested with Year 7 students.

Two-thirds of students responding to this question answered it incorrectly, and those students had an average ability level similar to that of students who answered correctly. This suggests that students were guessing, which prevented us from being able to use this question to discriminate between high- and low-performing students.

Also, the question did not fit with the overall test content or the other questions.

Although this is covered in the curriculum by Year 7, perhaps students were not familiar enough with the concept by the time they sat the test to be able to extend their knowledge to new situations, which is what the question requires. They may have had too little exposure to probability to apply it, with limited scaffolding, to a context that also required finding the difference between numbers, and could not confidently construct their own response.