Science in the early years: it’s a new lens on the future

ACER news 23 Jan 2024 7 minute readChildren who understand the world with a mind enriched by the habit of scientific inquiry have a gift that keeps on giving, Gayl O’Connor believes. That’s why the former biology teacher is helping educators to ‘tap into children’s natural curiosity’ and set the wheels in motion.

The early years represent the perfect time for science education to begin, Ms O’Connor, a Senior Research Fellow with the Australian Council for Educational Research, says.

This is partly because young children may be more willing than older children to take risks and accept mistakes – traits that are integral to scientific inquiry.

By regularly making discoveries through predicting, observing, revisiting their predictions and communicating their findings in pre-school and the first two years of primary school, children could grow into older students who are more receptive to further developing these traits, Ms O’Connor believes.

The importance of this becomes clear when considering that by year 3, children can already have common misconceptions – about things like gases, and mass in relation to size – that are highly resistant to change.

In undertaking a review of research into science teaching in the early years, Ms O’Connor saw a disconnect between the importance of fostering learning science content and scientific inquiry skills, and the tools available to early years educators to teach these with the same confidence they might approach reading or numeracy.

‘It’s not fair to expect people to jump straight into either an early learning centre or a primary classroom and know everything there is to know about science pedagogy,’ she says.

To support educators, she and fellow ACER researcher Christine Rosicka developed the Science in the early years resources.

Four years on, their free resources are more popular than ever, with up to 1000 downloads a month. And while they were originally linked with the first Early Years Learning Framework for Australia, they remain valid for the current version, ‘particularly because the resources suggest children’s progress be monitored over time, and assessment is explicitly considered now’, Ms O’Connor says.

‘What we want to do is establish science inquiry as being something that’s fun to do, and engaging, because it’s discovering things about the world around you, and that continues right through school, and ideally becomes lifelong.’

Speaking about the research findings that led to creation of the resources, Ms O’Connor says: ‘The big thing that came out of it was not to underestimate what children can do.’

Another critical review finding was that some educators lacked confidence in scientific teaching, while others were limited in their approach by focusing on specific domains.

In many early years' settings, there was good intentions without the resources or knowledge to follow through.

‘Some people like a science table in a corner, which I absolutely endorse. It may have magnifying glasses on it for kids to use to look at things like a beetle or a rock, but if you don’t give children direction, it can be a missed opportunity to build and hone further skills,’ Ms O’Connor says.

Resources that widen the scope

The resources include activities centred on things that are readily available – like a plant treasure hunt, where young children might draw a plant before having a closer examination of plants in their local area, and then compare their ‘before’ and ‘after’ depictions.

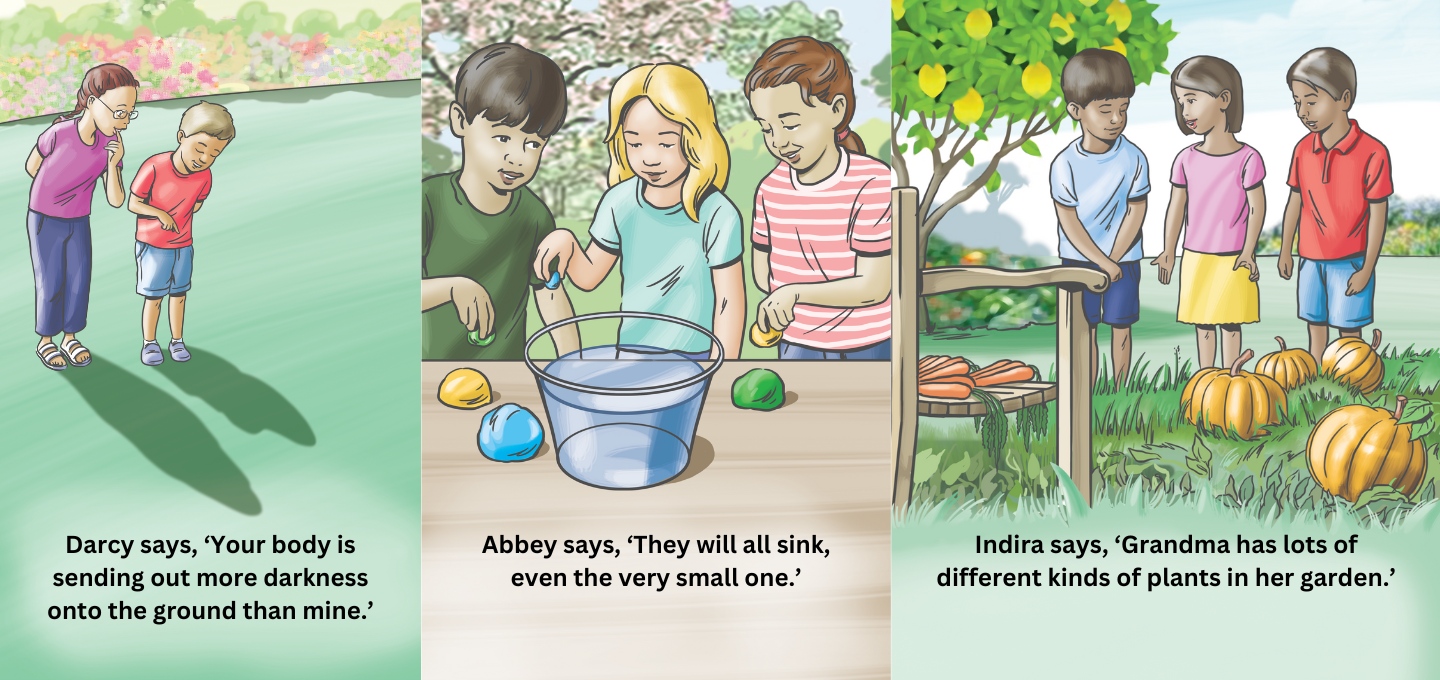

To support evaluation of understanding, there are also ‘concept cartoons’ for children to engage with and respond to. A scenario is posed, and the children provide reasons for which person’s statement is correct.

‘We provide background knowledge about the tasks, so educators have the science behind it at their fingertips if the kids ask curly questions, or if they want to encourage them further in asking why, to explain what they observe,’ Ms O’Connor says.

‘They might start by saying, “Well, why does a pine tree look like that? How is it different to a gum tree?” And then they might talk about classifications in a more formal way, because the information is there for them to do that.

‘It’s also entirely okay to say, “I don’t know – let's find out together”.’

Other activities look at floating and sinking, light and shadows, and exploring mixtures.

An eye on the future

The process of inquiry is largely the same one children will follow as they move into secondary school and beyond.

What will change as children get older, Ms O’Connor notes, is the sophistication around experimentation, variables and questioning of points of view. The topics might also include the ‘Anthropocene epoch’, or era in which human influence is having a great impact on the planet.

With the wellbeing of children in mind, Ms O’Connor believes the lens of scientific inquiry could reduce the potential for young people to become overwhelmed by issues like climate change.

For example, such a lens turns a conversation about the effects of car pollution into an inquiry about different technology and fuels, what might reduce the impact, and ways of measuring that.

‘If you’ve got an inquiring mindset, that helps you feel confident, and that in turn helps you feel more engaged with the world around you,’ Ms O’Connor says.

‘There’s that sense of hope for the future, especially for young people, so they can see things differently from early on; they can extend the world around them better and see that different actions will lead to different outcomes – that they do have agency and ways of changing the future.’