Cunningham Library is a research level collection for Australian education, and holds the most comprehensive and up-to-date collection of educational research documents in Australia.

Library collection

Cunningham Library is a research level collection for Australian education, and holds the most comprehensive and up-to-date collection of educational research documents in Australia.

The collection includes information relevant to all education sectors, including early childhood, schools, higher education, vocational education and training (VET), and professional education. The collection also includes some information relevant to psychology, counselling and human resources.

Our history

Who was Cunningham?

Dr Kenneth Stewart Cunningham was the founding director of ACER, a position he held for 25 years.

Cunningham was born in 1890 in Ballarat, Victoria, the son a Presbyterian minister and was educated in a variety of state and private schools in Victoria and Tasmania. In 1909 he began his teaching career in charge of a one-teacher school in an old selector's hut at Gunbower Island on the Murray River. In 1912 he was selected for a two-year primary teacher training course at the Melbourne Teachers College. He then transferred to secondary teacher training and started an arts course at the University of Melbourne in his second year.

In 1915 he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces in the Army Medical Service. He remained in the military forces until 1919, serving as a private and a lance corporal until eventually being appointed a lieutenant in the Army Education Service after the armistice.

In 1919 he resumed his studies, graduating in 1920. In 1920 he was appointed to the staff of the Melbourne Teachers College. He remained there until he was appointed Executive Officer of the ACER in 1930.

He came to this new job at the age of 40 with a background of practical experience in small rural schools, ten years of study and teaching in the area of research and experimental education, and some modest achievement in research on educational testing.

He retired from ACER in 1954 and took the opportunity to join a UNESCO mission working on teacher education. He died on 27 June 1976, aged eighty-six.

References: Connell, W. F. The Australian Council for Educational Research 1930-80. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research, 1980.

Cleverley, J. F. Research director and educator - K.S.Cunningham. In 'Pioneers of Australian Education: studies of the development of education in Australia 1900-50, volume 3' edited by C. Turney, pages 272-295. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1983.

Dr K.S. Cunningham: early years

with siblings c. late 1890’s

A pioneer of Australian education, Dr Kenneth Cunningham was the inaugural director of the Australian Council for Educational Research following its formation in 1929. A scholar, teacher, educator, researcher and author, Dr Cunningham contributed a great deal to the Australian educational landscape; a legacy that survives in the organisation today, and is honoured in the title of ACER’s very own resource repository, the Cunningham Library.

Born in Ballarat in 1890, Kenneth Stewart Cunningham was the second-oldest of the twelve children in his family. The son of Presbyterian minister, Cunningham taught himself to read at a young age by having his mother point out the words in church hymnals, before beginning his formal education at Goulburn Street School, Hobart in 1895.

Upon returning home from service, many returned service men and women found it difficult to resume study after such a lengthy break. Ever the academic, and quite possibly due to his educational activities whilst serving, Cunningham found that he suffered very little in this regard, and almost immediately returned to his studies. Particularly fascinated by the emerging subject of Sociology, and housing high academic aspirations, Cunningham completed his bachelors and masters degrees, and his diploma of education, with first-class honours, returning to the employment of the Education Department as a teacher.

Reluctant of his father’s wishes for him to join the clergy, Cunningham was fascinated by physiology and initially decided to pursue a career in medicine, however he soon found that the financial burden of university was too great. Despite holding a job as a private tutor, and in a fortunate turn of events for Australian education, Cunningham was forced to pursue an alternate career path, applying for a position with the Victorian State Department of Education. Teacher shortages at the time allowed for Cunningham to be accepted as an adult entrant, and after a short course (less than a year) which included observation rounds and teaching lessons under observation, Cunningham took up his first educational appointment as a temporary assistant in charge of the school on Gunbower Island on the Murray River in 1909.

In a sign of things to come from Cunningham’s life and legacy, it is reported that in his earliest years of work his sympathies for the less fortunate in Australian society came to the forefront, as did his penchant for research and obtaining knowledge. As a young teacher, Cunningham carted a tin trunk full of books around the countryside (being placed at a variety of schools over a five year period) and studied at length each evening. On the relieving staff at a rural school in 1911, he noted that many rural children were tired after long journeys to school and many chores at home – and that many school inspectors were unsympathetic towards this handicap, despite its obvious effects on learning.

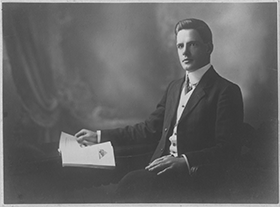

man in the years leading up to

World War One

Cunningham moved on from his positions in regional areas to train further at the Melbourne Teacher’s College in 1912, where he developed an interest in psychology and intelligence testing. On being exposed to the theories of the 'new education' movement and intelligence testing, he gained an increasing appetite for reading about overseas trends. He also came under the influence of the principal at the time, Dr. John Smyth, who permitted him to pursue secondary teaching studies at the University of Melbourne, where he completed his BA in 1914, before accepting a position at the Bell Street Fitzroy Special School for Feeble Minded Children. This school, the first of its kind in Australia, was a project of the Victorian Director of Education, Frank Tate, and was headed by inventive psychologist Stanley Porteous – both men with whom Cunningham would come to enjoy important personal relationships with, and who were integral to his later appointment as the first director of the Australian Council for Educational Research following the end of the First World War.

The school itself devoted a portion of its time to the testing and study of students, in particular a study of the correlation of the Porteous Maze Test and the Stanford Revision of Binet based on the study of 100 Victorian students, which would lead to Cunningham’s first published work, which appeared in the Journal of Educational Psychology in November 1916.

The four years Cunningham spent as a college and university student combined with the eight months at the Bell Street School had been the most productive period of his life. As a high achieving, studious and systematic young man, he had made a rapid transition from partly qualified country school teacher into a promising young academic. In the shadows of World War One, as he prepared to don an army uniform for the first time, he had no way of knowing the profound effect war, tragedy and bearing witness to loss of life would have on his life, nor the way it would move through him to shape the landscape of Australian education.

References

Williams B., Education with its eyes open 1994, ACER Press, Camberwell, VIC

Turney C., Pioneers of Australian Education , Vol. 3 1983, Sydney University Press, Sydney NSW

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 13, (MUP), 1993, Australian National University, Canberra ACT

Dr K.S. Cunningham: A scholar goes to war

News of the landing at Gallipoli in April of 1915 saw a significant rise in recruitment figures across Australia. While early recruits had joined primarily to satisfy a yearning for adventure, many later enlistments were motivated by rising casualty lists and a growing sense of necessity. In August of the same year, twenty-five year old scholar, academic and teacher Dr Kenneth Cunningham became an enlisted man in the service of his country, and was given first-hand experience to the horrors of war and the trauma of loss.

Leaving his teaching post at the Bell Street School, Cunningham initially joined the infantry, but still housing some prior want of a career in medicine, soon transferred to the Army Medical Corps (AMC). As a trainee stretcher he undertook training in and observed a variety of medical procedures, and performed general duties at the local hospital.

Cunningham wished to rise to the highest rank possible while serving his country, and was disappointed to learn that the best a non-medical serviceman could hope for in a field ambulance unit was sergeant or warrant officer. He was dismayed at the Australian rejection of the British custom of automatically sending infantrymen with a University education on to officer training school, feeling that Australian medical graduates were particularly fortunate as they received commissions on enlistment and could expect rapid promotion. The advantage of medical graduates entering into the AMC not only heightened Cunningham’s frustration at his earlier inability to study medicine, but also led him to assume that in some cases, unsuitable men had command over others in the ranks.

Despite his initial frustration with the system, Cunningham was selected to attend officer training school at Broadmeadows beginning in January of 1916. He attended for the required thirty days, completing the courses successfully and achieved sufficient results for a nomination to the officer’s college at Duntroon, however this opportunity failed to materialise before Cunningham’s company were shipped out to join the Western Front in France, and was inadvertently lost to him.

After Gallipoli the majority of the Australian Infantry Force (AIF) were sent to this front to fight the advancing German army. Between July and September 1916, the AIF was engaged in the battle of the Somme and experienced some of the bloodiest fighting of the war, sustaining nearly thirty thousand casualties.

Cunningham arrived in a section of the war completely ravaged by carnage and bloodshed. The advent of the machine gun had allowed for the massacre of wave after wave of advancing forces, while tanks and explosive artillery, unperturbed by barbed wire and obstacles to foot-soldiers allowed for devastating long-ranged attacks.

Joining the 5th Field Ambulance unit as a stretcher bearer, Cunningham struggled with the futility and seemingly senseless destruction of war; retaining many of his scholarly practices, Cunningham wrote fervently from inside trenches at the front, seemingly seeking refuge from his surroundings in his writings. Often writing at night, by the light of a candle he had dug into the side of the narrow trenches, Cunningham observed the condition and weariness of the men returning from the front.

As a regimental stretcher bearer his duties required him to retrieve the wounded from the maze of trenches composing the front and return them to makeshift first-aid posts, where they were given rudimentary medical attention. The exposure to troops returning from the front and their recollections from the fighting were scribed in Cunningham’s journal. Vividly describing shell-shock and the toll the war was taking on the soldiers in his care, Cunningham recorded the words of one particular soldier who had previously seen action at Gallipoli, exclaiming that he would rather endure six months there than a single week amongst the fighting on the present front.

In July of 1916, Cunningham was moved to a front beginning a series of attacks on the derelict French village of Pozières - a battlefield later described as ‘more densely sown with Australian sacrifice that any other place on earth’. Under the constant duress of enemy fire, Cunningham’s squad ferried critically injured soldiers through fields encumbered with debris and the concussions of exploding artillery. These recues could sometimes last several hours as the stretcher bearers hauled patients through the narrow enclaves littered with shrapnel and the bodies of the fallen. Cunningham believed it to be the hardest physical work under the most terrible conditions he could ever expect to endure, a thought he epitomised in a letter back home:

“If I believe that hell was a matter of physical torture I could not imagine it worse than this place.”

Adding to his written lamentations on the front and on the horrible business of war, while on a ‘carry’ Cunningham came frighteningly close to losing his own life, as a piece of shrapnel from nearby exploding artillery shells lodged itself in the buckle of his stretcher sling. Had he not been wearing the sling, the shrapnel would have pierced his heart.

Toward the end of 1916, Cunningham penned a lengthy essay from a rain-soaked trench near Delville Wood. Entitled “Life Versus Death” Cunningham outlined the repulsiveness of stumbling across bodies of the fallen and the overwhelming magnitude of the death caused by war. He clearly came to despise conflict, but showed a determination that the sacrifices it brought about should not be for nought;

“It rests with those who remain to prove themselves worthy that blood should be poured out so that they may remain in peace and security; above all it rests with them to see that any repetition of this sacrifice of life is rendered impossible”

Despite his lament for his surroundings and his chronicles of the bloodshed, Cunningham also made notes on educational practices within the armed forces. Due to the young enlistment age, many soldiers fell behind educationally and some knew no calling except the army. This was a point of frustration for Cunningham as an educator, who felt that the lack of education apparent in the trenches led to soldiers losing the ability to view events objectively, taking rumour and hearsay for news without substantiation.

In 1918 Cunningham began an involvement with army education, when his commanding officer asked for his co-operation in organising a unit scheme of classes and lectures to offer the men some mental stimulation. Pre-dating the official AIF Education Service, Cunningham put together a series of lectures on shorthand, math, biology and grammar – many of which were welcomed by the troops in his unit.

The success of this scheme buoyed Cunningham to apply for a course in Cambridge for men believed to be capable of contributing to the expanding area of military education. Despite being overlooked for this particular course, Cunningham’s contribution was rewarded with a commission in November of 1918, rising to the rank of lieutenant and becoming Education Officer for the three ambulance units in the 2nd Division.

Upon his appointment, Cunningham was able to obtain an office at Divisional Headquarters, finally putting an end to his horrifying time on the front lines. He served out the remainder of the war in his position as Education Officer, before arriving back on Australian soil in 1919. Completely changed by his wartime experiences, but still a young man, Cunningham adopted an unflinching belief in the futility of war and its senseless toll on humanity, society and education – a hard-learned perspective that would continue to shape his next and most famous contribution to Australia – as the inaugural director of the Australian Council for Educational Research.

References

Williams B., Education with its eyes open 1994, ACER Press, Camberwell, VIC

Turney C., Pioneers of Australian Education , Vol. 3 1983, Sydney University Press, Sydney NSW

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 13, (MUP), 1993, Australian National University, Canberra ACT

The birth of ACER

Following his return from the war in 1919, Dr Kenneth Cunningham found that the war efforts had made new demands on the Australian economy and significantly altered the place and value of education and testing, triggering his significant interest in and contribution to education in Australia.

During the 1920s, amid substantial industrialisation and urbanisation taking place in Victoria, widespread testing of Victorian school children became an accepted practice; the value of education was beginning to be realised as industry increasingly called for skilled labour. This increased emphasis on education and its role in shaping an efficient and productive workforce created a need for new methods of testing, assessment and delivery of curriculum across primary and secondary schooling and gave rise to the emergence of a new organisation on the Australian educational landscape, the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER).

Upon returning home from service, many returned service men and women found it difficult to resume study after such a lengthy break. Ever the academic, and quite possibly due to his educational activities whilst serving, Cunningham found that he suffered very little in this regard, and almost immediately returned to his studies. Particularly fascinated by the emerging subject of Sociology, and housing high academic aspirations, Cunningham completed his bachelors and masters degrees, and his diploma of education, with first-class honours, returning to the employment of the Education Department as a teacher.

His tenure as a post-war classroom teacher was short-lived, as shortly after resuming his teaching duties he was offered a position as acting Master of Method (Primary) at the Melbourne Teachers’ College, replacing a recently promoted lecturer. Students in experimental education, under Cunningham’s tutelage, were given lectures on the significance of intelligence tests, memory processes, types of imagery and statistical methods. Cunningham also gave students practical demonstrations in testing, and expected them to conduct their own experiments. From his work at the Melbourne Teachers’ College, Cunningham was also appointed to part-time lecturing positions at the University of Melbourne, demonstrating the respect the educational community were beginning to have for his academic credentials and qualifications.

Continuing an upward rise through the education community, in 1923 Cunningham was appointed head of an educational psychology laboratory, conceived by Dr John Smyth. The emphasis of the work conducted by the laboratory was on intellectual deficiency and mental testing; training teachers to apply tests; and giving demonstrations in experimental work. Cunningham believed that testing and measurement of intelligence had a very practical application and could be administered to make teaching more effective, thus enabling a more calculated delivery of education that better served the needs of the child. As head of the laboratory, Cunningham’s professional status increased and he came to be seen as something of a local expert on testing, educational psychology and individual differences.

In 1925, Cunningham was awarded a Macy Scholarship – an award made available for a prominent educator from outside the United States to attend the Teachers’ College at Columbia University in New York. Accepting the scholarship, Cunningham studied at Columbia University until 1927, under the tutelage of John Dewey, Edward Lee Thorndike and Isaac Kandel, and completed his PhD in only 14 months – one of the shortest candidatures on record at Columbia. At the time, most American educational research focussed on educational surveys and curriculum construction, and Cunningham found that American education was being surveyed and examined in a myriad of different ways and directions, noting (quite clairvoyantly given his own future):

It cannot be doubted that such surveys of Australian education will become far more common in the future. They will help to remove the present lack... of knowledge of Australian standards and achievements in education, a lack of which is due to our own failure to carry out and publish some studies

and

‘There is here a whole field of educational study which as yet has scarcely opened up in Australia, at least as forming part of organised educational study and research.’

While at Columbia, Cunningham had mixed freely with the top echelon of America’s progressive educational thinkers, and returned to Australia with a distinctly pro-American outlook, returning to his duties at the Melbourne Teachers’ College in April 1927.

On 4 July of the same year, Frank Tate, Director of Education in Victoria, requested Cunningham’s assistance on a lengthy application to the Carnegie Corporation for a grant to facilitate the ‘Australian Institute of Educational Research’ – with a particular emphasis on the advantages of a centralised system for the collection of research data. Tate believed that the new entity could model the pre-existing ‘Council for Scientific and Industrial Research’, which had a strong committee in each state, and an executive of three members to determine its policy.

The proposal was met favourably, with an assurance that once an organisation ‘capable of administering funds and of directing scientific investigation’ was founded the Carnegie Corporation would grant £50 000, payable in instalments from 1 January, 1930.

Over the next three years, Tate met with a committee comprised of himself, Henry Lovell and Alexander Mackie, along with various state representatives, securing their cooperation in the formation of the new entity. On 5 August, 1929 the delegates agreed on the creation of the role of ‘executive officer’ for the new institution.

Although the institution was to be formally constituted in February 1930, the existing stakeholders took immediate steps to appoint an executive officer. The position was widely advertised and attracted an impressive list of applicants. By the close of applications on 24 January, 1930 Cunningham was one of 10 aspirants for the position.

Through his academic achievements and work in education since returning from the war, Cunningham’s application was strong, outlining his belief in the possibilities of educational research, and his determination, if appointed, to ensure that the new research organisation would perform the important functions in Australian education ‘which appears to lie before it’.

The field was narrowed to three candidates before a preferential ballot identified Cunningham as the inaugural executive officer of what had by now come to be known as the Australian Council for Educational Research.

With Cunningham installed as the executive officer, ACER officially commenced work on 1 April, 1930, attracting considerable publicity from news outlets. On April 5, 1930 Cunningham published an article in the Herald entitled ‘Education with its eyes open’ – a title he also used on a 15-minute radio broadcast with ELO – and through which he expressed one of his earliest visions for the newly founded organisation:

‘We must aim at an education which will use every possible means of critically testing its data, its methods, and its results; which will not stick like a limpet to the rock of tradition, but will move forward with its eyes open.’

That sentiment has echoed through the ongoing work of ACER and its mission to improve learning in education from the point of its inception to the present day.

References

Williams B. 1994. Education with its eyes open, Melbourne: ACER Press.

Turney C. 1983. Pioneers of Australian Education, Vol. 3. Sydney:, Sydney University Press.

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 13. 1993. Canberra: Australian National University.