Loading skills with the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge

ACER news 24 Oct 2023 9 minute readWinners of the 2023 Australian STEM Video Game Challenge discuss the steep learning curve, and highs and lows of creating video games.

‘The mind that opens to a new idea never returns to its original size.’ – Albert Einstein.

When you’re mesmerised by moving images on a screen, it all looks easy. What it takes to create those images is a different story – one of planning and process, trial and error, learning on the fly, pivoting and perseverance.

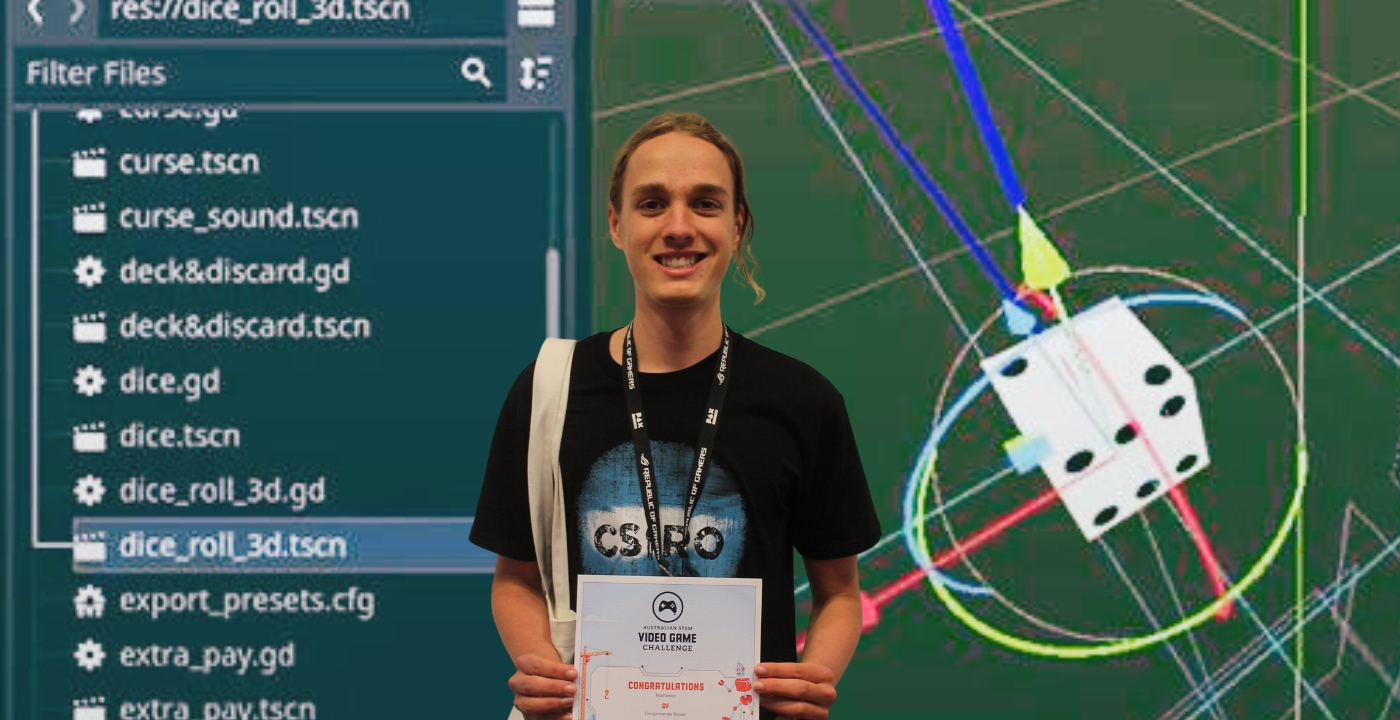

It is an endeavour that year 10 student Mathieson loves pursuing through the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge, a game design competition facilitated by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) since 2014.

Mathieson undertook the coding for his team’s game ‘Battle of Batone’ that won a category in the 2023 challenge. When he talks about the process, it becomes apparent that much of the thrill is in his understanding that he is teaching a computer how to use human knowledge.

‘With how much I’ve learnt over 2 terms, I could do the game now in half as long,’ Mathieson says. ‘It’s not just about games; you could apply this to all sorts of other careers, like medical research.’

The aim of the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge is to empower the next generation of problem solvers by providing a fun and authentic learning opportunity that engages with science, technology, engineering and mathematics subjects (STEM) and could lead to STEM careers. More than 800 students from years 4-12 took part in 2023 either as individuals or teams, with schools and mentors resourced to support them.

Registrations are open for the next Australian STEM Video Game Challenge and will remain open until 22 July 2024. The theme is ‘stars’ – with lots of possibilities, including space, geometric shapes, art and pop culture.

Lisa van Beeck, the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge project director, says the challenge approach has been designed to support 21st Century skills.

‘Entrants who take part will be called on to develop and use many of the skills that are required for further study and careers in STEM,’ she says.

‘The Australian Video Game Challenge is incredibly valuable in contributing to the STEM pipeline at a time when jobs requiring STEM skills are growing at twice the rate of other jobs.’

A chance to see what you can be

Mathieson is talking at a stand for the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge, where ‘Battle of Batone’ and other winning entries are being trialled by game lovers. It is in a prime location at the PAX Australia gaming festival, close to Nintendo and other industry leaders, in a maelstrom of costumes, colour and sound.

He has travelled from remote Queensland with his family, including collaborators Isla (year 7), Michael (year 11) and Sonny (year 9) who shares: ‘There are more people in one square metre here than there are in our whole town’.

It is the second year that Mathieson and his brothers have won a category, with Michael progressing the narrative and Sonny doing the sound effects. Sonny, a creative writer by choice, adapted his style to complete the required Game Design Document (GDD) and says he is more confident in technical reporting now.

Isla, 12, contributed for the first time after teaching herself new digital applications to create character faces, animations and game card illustrations.

'I had to learn to use the iPad because it was completely new to me; I watched YouTube videos and tutorials and I just got better at it.'

Independent developer Matty Davis, teacher/mentor Daniel Edwards, Mathieson, Cynthia Gusman-Nolan (Queensland's Gateway Industry Schools Program), Isla, Michael and Sonny following a panel presentation at PAX Australia.

Independent developer Matty Davis, teacher/mentor Daniel Edwards, Mathieson, Cynthia Gusman-Nolan (Queensland's Gateway Industry Schools Program), Isla, Michael and Sonny following a panel presentation at PAX Australia.

Michael says: ‘All of our talents made it. Everyone put so much effort and work into it, it was amazing.’

Living around 600km from Brisbane and homeschooled, the siblings entered the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge with their mother Jillina as their official mentor, setting meetings and agendas.

‘There were some dramas,’ Michael says. ‘Four siblings working together and with mum; things can get heated. We had to put aside our differences and come together – but later,’ he says with a wry smile.

Dee, 14, a Melbourne student also at PAX as a winner of the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge, had to overcome moments of extreme frustration in building her game Elementary.

In keeping with the 2023 theme of Construction and Deconstruction, she gave players the ability to build high towers while trying to avoid their collapse. Her sticking point was finding a way to clone the different sized and coloured blocks.

The frustration of failure was so strong that when Dee had a breakthrough, she almost didn’t recognise it.

‘When I was testing it, I did it with the red block,’ she says. The game didn’t crash, which was good, and when the second block fell, I went “No” because I’d never seen it before but then I realised it had worked.

‘You do get lots of good satisfaction when you finally fix something that hasn’t worked.’

Dee tests her game 'Elementary' at the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge stand at PAX Australia.

Dee tests her game 'Elementary' at the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge stand at PAX Australia.

Skills for STEM careers already on show

The skills the students developed reflect those identified in the Power of Play report that analysed survey responses from almost 13,000 game players (aged over 16) in 12 countries, including Australia.

The report shows 69% of players believed video games build problem-solving, cognitive, teamwork and collaboration skills, 65% felt they promoted adaptability, and 60% felt they advanced communications skills.

They also align with the skills identified as important by tertiary students studying STEM subjects, according to new research from Taiwan that recognises graduation of STEM students as a global priority. The ability to manage time, perform quantative/mathematical tasks and delegate were seen as important, with many students also saying they found writing reports difficult.

The study refers to ACER findings that ‘science and engineering students often rely on deep memorising strategies or focus on operational steps and procedures’. The experiences of entrants in the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge suggest the learning can be deep on several fronts, as Mathieson reveals in describing his approach.

He speaks quickly in his eagerness to help others understand how ‘Battle of Batone’ – based on a card game that Michael created as a Christmas present – has become digital entertainment.

‘It’s just physics,’ Mathieson says of incorporating a dice toss into the program. ‘Instead of having the computer select a number and then the dice roll based on what the computer selected, I made it a physics thing. I took an object that is 3D and put it into a 2D world.’

He built a roof, and walls for the die to bounce against, so they didn’t disappear off the screen, making them invisible so as not to interfere with the aesthetic.

His next challenge was how to get the computer to read a number on the top of a 3D dice ‘because the computer can’t see the way we see’. At some point, Mathieson introduces the relevance of ‘infinite laser beams’ coming off each face of the cube.

‘You get the computer to pick a random angle and drop it so you get a random roll and whatever face is connected to the ray and hits the roof, that’s the face that gets read.’

Despite the challenges, and perhaps because of them, the winners recommend taking on the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge to other students.

‘It’s a really fun way to do STEM stuff,’ Mathieson says. ‘It’s a great introduction to it.’

Find out more: