When students feign interest: new research shows how to get them back

Research 13 Jan 2025 8 minute readYoung people have told researchers how they withdraw from learning, but also what helps them to invest in it, contributing new insights for improving student engagement.

A study of more than 1,200 Australian students shows that while 40% of those in primary school strongly agreed they were good learners, less than half this number (18%) believed this of themselves in secondary school.

Overall, 28% of students described challenges in their learning, with common responses including feeling disengaged and demotivated, finding work too hard, feeling unsuccessful and being distracted.

Many also described learning as a passive experience in which they had little ability to make decisions.

These and other vital insights into how students think and feel when learning have been captured by a special Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) research project.

Critically, students also shared the ways they drive their own learning, and when they feel in control of that.

What did the research cover?

ACER researchers Dr Amy Berry and Dr Kellie Picker worked with co-educational and girls’ and boys’ schools in the government and Catholic education sectors in Melbourne to gather the student views through online surveys and focus groups in 2023.

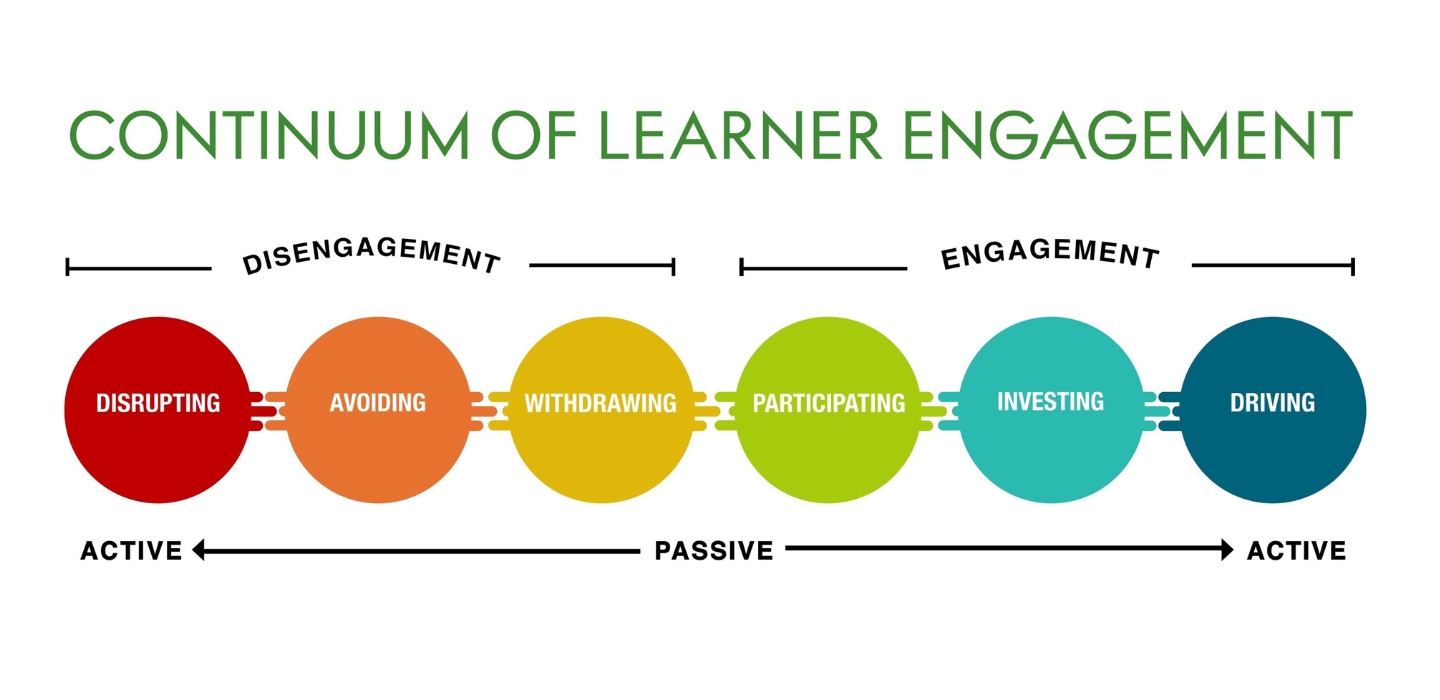

The new research has provided the opportunity to test and refine The Continuum of Learner Engagement, a resource originally developed in 2020 and available to teachers and schools interested in improving student engagement in learning.

The continuum (as below) was based on teachers’ experiences, and will now be revised to reflect the student voices captured.

How students described being engaged in learning

The revised model is expected to include new indicators of what engagement and disengagement look like, as described by students.

For example, sharing ideas and being curious are noted as an indication that a student is investing in their learning, while asking for feedback and seeking help when needed points to a student driving their own learning.

Those invested in their learning expressed feeling excited and motivated to learn, with secondary students describing it as feeling ‘inspired’ and primary students feeling ‘sucked in’ by what they were learning during a lesson.

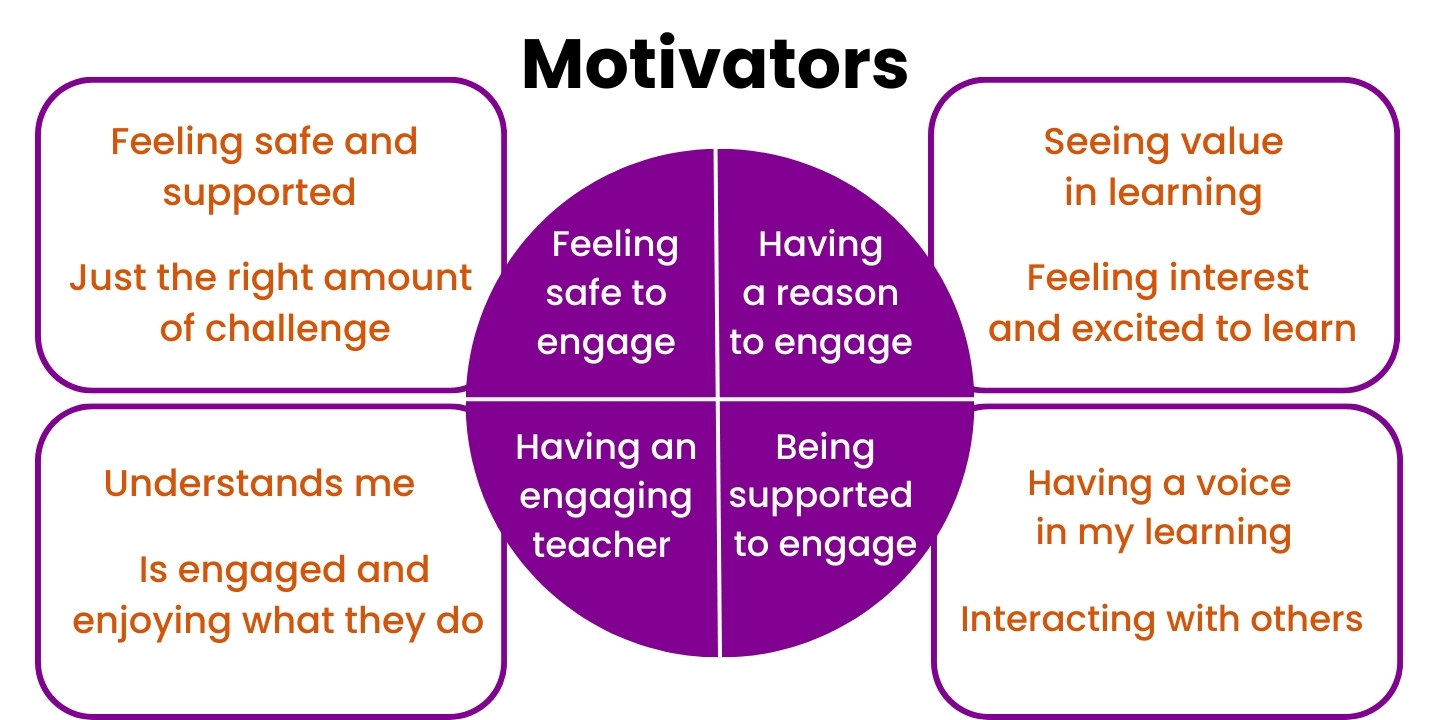

Enjoyment of learning commonly centred on connections with teachers and friends, feeling safe and supported, learning experiences that were fun and interesting, having a say, valuing what they were learning and feeling capable of taking on challenges.

A year 10 student shared:

‘I just really enjoy the environment … because of the great teachers and peers that go to my school. I also just really enjoy learning things and expanding my knowledge.’

How students spoke of being disengaged

Focus groups pointed to similar responses from primary and secondary students when talking about withdrawing from learning – including ‘faking it’, ‘zoning out’ and thinking about other things.

Some secondary students also mentioned having ‘headphones on and listening to music secretly’.

Dr Berry has had first-hand experience of working with disengaged students – as a teacher whose roles included being in charge of the ‘naughty kids’ room’ at one school – and also in working with pre-service and in-service teachers grappling with the 'persistent and significant challenge' of supporting their students to engage in learning at school.

‘One of the challenges of working in this space is that people often make no distinction between engagement in school and engagement in learning. They are related, for sure, but it’s not the same thing,’ she says.

‘Another challenge is that passive disengagement is often a blind spot for teachers because those kids do not present a threat to the smooth running of the lesson. But it is a serious issue for learning.

‘The negative impact of disengaging from learning is the same whether a student chooses to actively disengage or passively disengage. Either way, they are turning away from the opportunity to learn rather than towards it.’

‘It can also have an impact on high-ability children who are just ticking boxes; they might be sitting in withdrawal mode and not really learning because they know they can still tick those boxes and get by.’

As one year 4 student shared: ‘I think I’m a good learner because I do what I need to do at the expectation. I just participate; I don’t drive or invest. I don’t go for really good; I just go for good enough.’

Of concern to Dr Berry is the finding that many students felt being good at learning was about finding things easy, being quicker than others, achieving a certain grade or standard, and staying out of trouble.

What students want

Students provided tips for teachers to increase their engagement, including mixing things up, showing interest and passion in what they’re doing, being patient and fair, and giving them ‘a chance to take the driver’s seat’.

A year 8 student offered this advice: ‘We’re capable of doing a bit more than people think and even if we don’t really get good grades, it doesn’t mean that we’re not capable … we just want to be excited and curious about what we’re doing.’

Why the research matters

Dr Berry says while there is strong evidence that engagement is linked with higher performance, it remains a pervasive and persistent challenge within schools.

She and Dr Picker expect that an enhanced continuum of engagement will be a powerful tool for more effective learning, not only for teachers, but also for students.

‘Much of what we do as a teacher is designed to connect students to the curriculum but learning comes down to how well they can engage in the process of learning,’ Dr Berry says.

‘We know kids have to be actively involved in this process. If they don’t feel that it’s within their power to manage their engagement during learning, they will remain forever reliant on the teacher to manage it for them.

The work may be particularly important for some students – including those who have limited support at home or students with additional needs – because they may be more vulnerable to the variations that come when working with different teachers, Dr Berry says.

‘Ideally we want kids to be empowered and equipped to monitor their own engagement so they can check in and see if they’re drifting into disengagement and be able to answer the question, how do I get back?’