How students performed in PISA’s 8 essential maths skills

Research 11 Mar 2025 10 minute readThe Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) has conducted its deepest dive yet into what Australian 15-year-olds knew and could do in maths in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2022. Lisa De Bortoli and Catherine Underwood share some surprising findings and persistent inequities.

Thinking about the way students learn, and the maths knowledge they need, evolved considerably in the decade since maths was last the main focus of PISA.

PISA 2022 was designed to meet the shared expectations of 81 participating countries and economies in assessing around 690,000 15-year-olds, representing around 29 million students.

Frameworks reflected new goals for education and new hopes for how education can prepare 15-year-olds for their future in increasingly complex environments.

In maths, updates recognised the increasing use of computing tools in everyday life, and positioned mathematical reasoning as integral to maths literacy.

This was significant, given the range of skills mathematical reasoning requires, including the ability to evaluate situations, choose strategies, draw logical conclusions, develop solutions and know how they could be applied.

In PISA 2022 A closer look at mathematics in Australia, we’ve reported on a number of significant variables to see how students were able to understand and resolve situations mathematically.

What the report analyses

ACER’s new report provides insights on 2 distinct areas of maths skills tested by PISA. The first measures student knowledge of content, covering Change and relationships, Quantity, Space and shape, and Uncertainty and data.

The second measures the thinking required for effective problem-solving in maths, covering Formulating situations mathematically; Employing mathematical concepts, facts and procedures; Interpreting, applying and evaluating mathematical outcomes; and Mathematical reasoning.

The combination shows us how students are using skills that are foundational for competency in everything from shopping, preparing food and managing personal finances, to future pursuits in fields such as ecology, climate, medicine, genetics and space science.

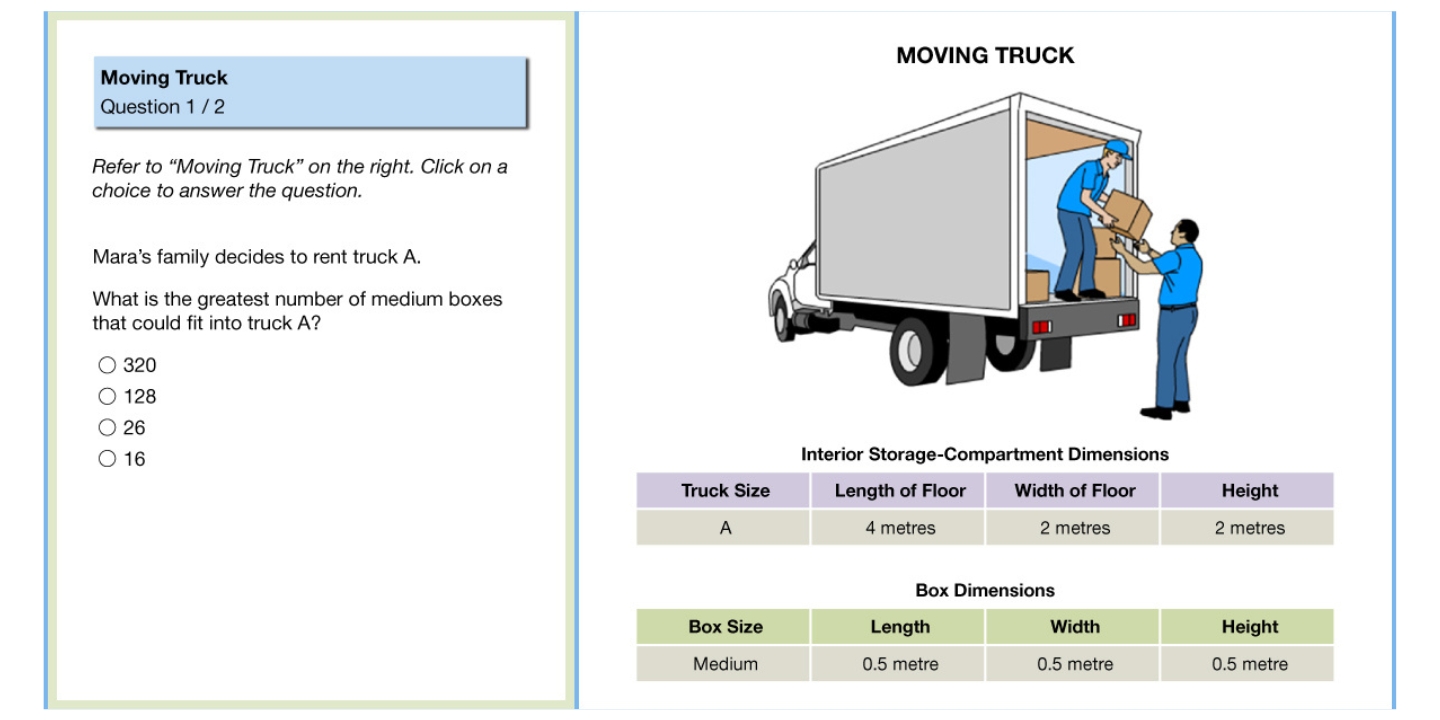

The question below is an example of one used to test students' understanding of space and shape and how they employ mathematical concepts.

Additionally, questionnaire responses analysed in the report give us an overview of the impact things like confidence in maths abilities can have on performance.

How did Australian students do?

More than 13,430 Australian 15-year-olds took part in PISA 2022.

The average Australian student performed above the OECD average in all maths content areas, showing the greatest strength in Uncertainty and data.

The average girl and boy both performed above the OECD average for their gender.

We also had a larger proportion of high performers and a smaller proportion of low performers than the OECD average in knowledge of maths content.

In thinking skills, the average Australian student also performed above the OECD average, showing the greatest strength in Interpreting, applying and evaluating mathematical outcomes.

Alongside this, inequities found in our previous reports were confirmed at almost every level the data was interrogated.

For example, in each of the content areas, around one in 4 students in major cities was a low performer, compared to almost one in every 3 students in regional locations and close to one in every 2 in remote areas.

Disadvantage also had an impact; each quarterly increase in socioeconomic advantage saw an increase in the percentage of students who met the national proficient standard, and the percentage of high performers.

Because of this, perhaps the greatest strength of our new report is in the detailed view of different demographic groups – how they felt about maths, and how they were able to use it.

It shows the proportions of each group that excelled and struggled, and indicators of where targeted support could benefit future students in developing these critical skills.

What does the report find on the gender gap in maths?

This analysis gives us crucial insights across each of the 4 content and thinking process areas, and also points to influences and exceptions.

Boys outperformed girls in PISA maths in most measures in 2022. Significantly, we found that 57% of Australian girls, compared to 70% of boys, felt confident identifying mathematical aspects of a real-world problem.

We have also identified, nationally, where girls matched the performance of boys – in Interpreting, applying and evaluating mathematical outcomes.

Our report shows where the gender gap is largest and smallest, with the ACT showing a relatively small gender gap in performance.

It also finds that in Tasmania, where scores were generally lower, girls are bucking the trend; the mean score for girls was higher than that of boys in 3 of the 4 content areas (Uncertainty and data, Quantity, and Change and relationships).

Where confidence had an impact

We know that confidence also plays a part in maths performance.

For this report, ACER created an index covering maths reasoning and 21st century maths, which encompasses creative thinking, logical reasoning and problem-solving for real-world application.

In these areas, we found that girls, disadvantaged students, those in regional and remote areas and First Nations students all reported lower confidence and self-belief in their capabilities than boys, those from advantaged backgrounds and those living in major cities.

On the index covering student belief in their mathematical reasoning skills and 21st-century maths, students in the highest quarter scored 95 points on average more than students in the lowest quarter. This score point difference was equal to nearly 4 years and 3 months of schooling.

Those experiencing the greatest maths anxiety were similarly impacted, performing almost 4 years behind those experiencing the least.

But the depth of our analysis shows us that the experience of these groups is not the same in every situation.

How student experiences relate to confidence

One of the biggest differences in confidence reported by advantaged and disadvantaged students was in extracting mathematical information from diagrams, graphs or simulations, where 84% of advantaged students and 59% of disadvantaged students felt confident to do this.

A greater proportion of advantaged students than disadvantaged students (76% compared to 51%) also expressed confidence in evaluating the significance of observed patterns in data.

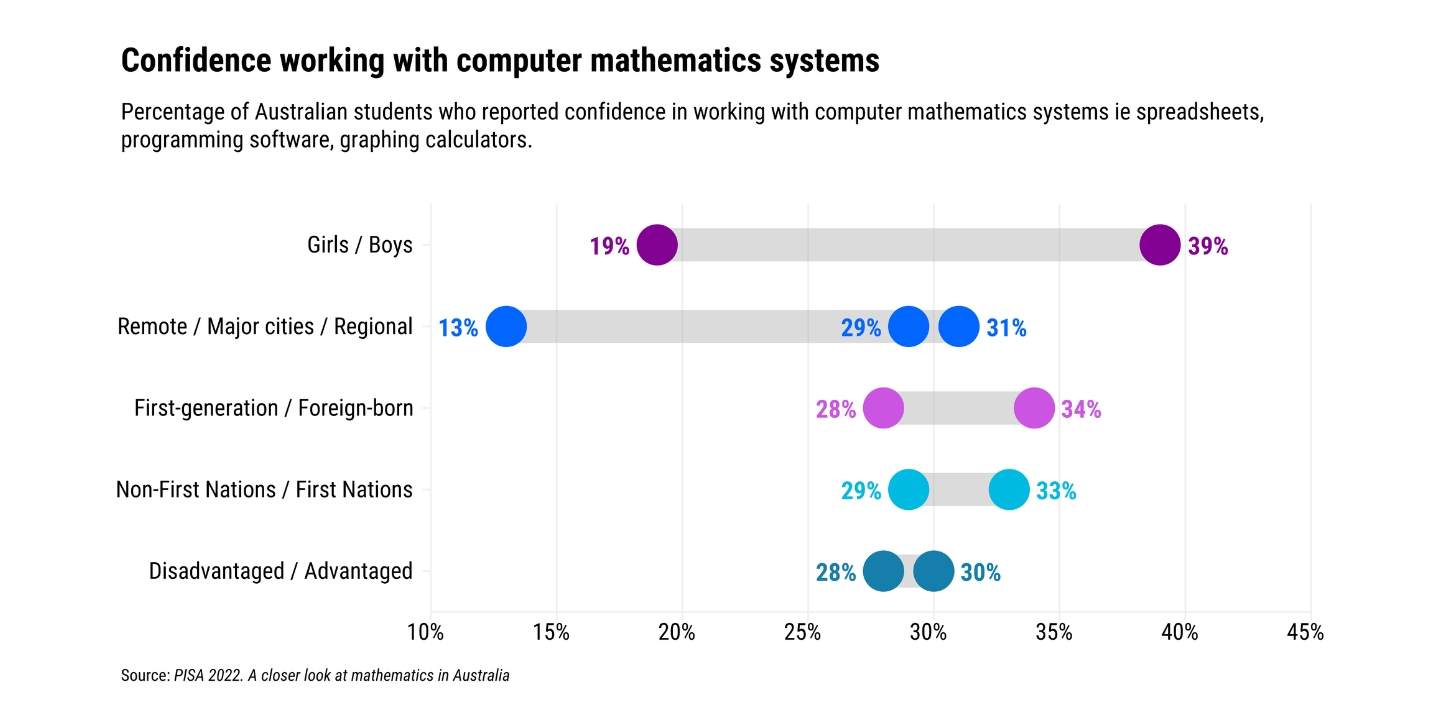

Conversely, there was almost no difference in the confidence of advantaged and disadvantaged students when it came to working with computer mathematics systems such as spreadsheets, programming software and graphing calculators.

There was also no significant difference in how First Nations and non-First Nations students felt about using computer mathematics systems.

With this activity, gender and geography provided the greatest contrast in experience and attitude.

Lower proportions of girls than boys (19% compared to 39%), and lower proportions of students in remote locations (13%) compared to those in the regions (29%) and major cities (31%) were confident in using computer mathematics systems.

Girls were also significantly less confident in coding and programming computers than boys (46% compared to 61%).

The situation for each of these groups was different again when looking at classroom behaviours in maths.

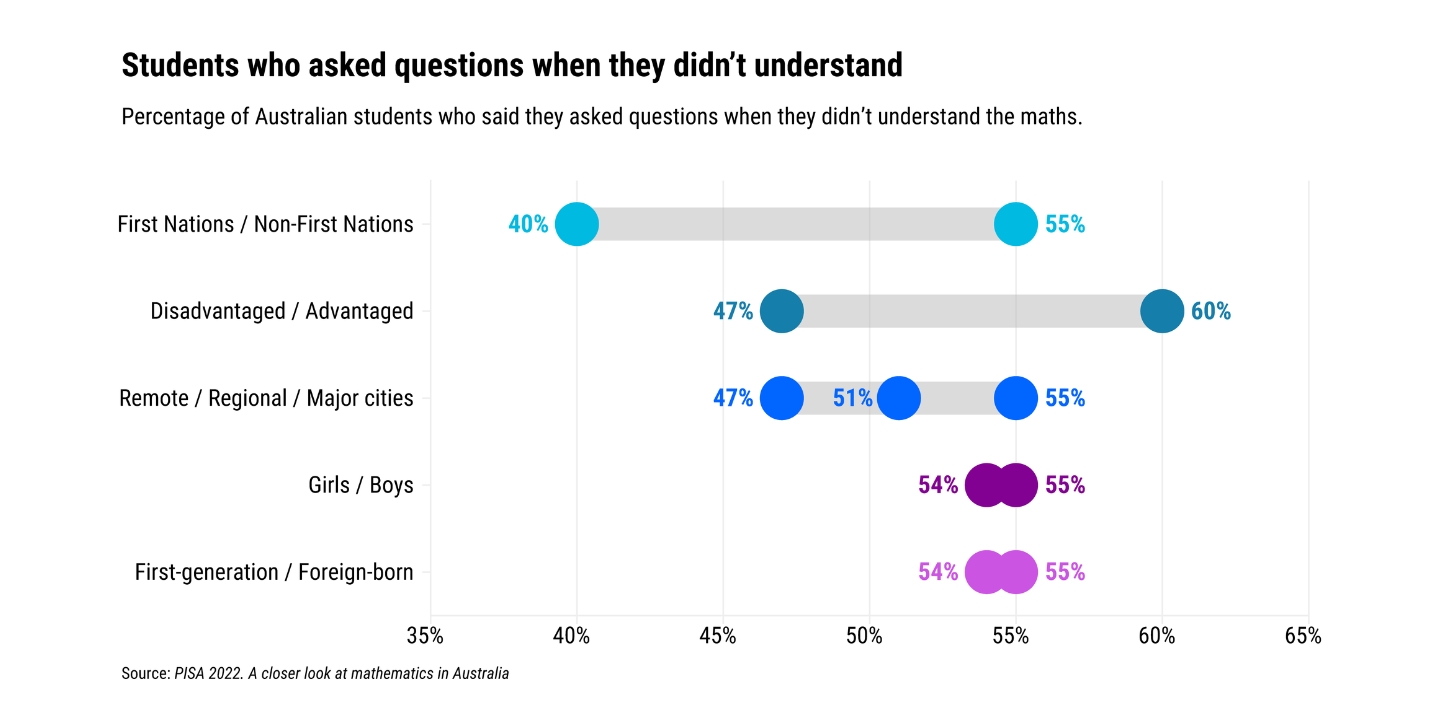

Similar percentages of boys (55%) and girls (54%) reported asking questions when they didn’t understand the maths being taught, and there was little variation found when looking at where students lived.

A wide gap was found when comparing the proportions of disadvantaged students who asked questions (47%) with the proportion of advantaged students who reported this behaviour (60%).

The gap was also significant when looking at the proportion of First Nations students who asked questions (40%) compared to non-First Nations students (55%).

A wealth of findings from PISA to support teaching and learning

For students to be mathematically literate they must be able to recognise the mathematical nature of a problem or real-world situation, formulate it mathematically and then use the mathematical concepts, algorithms and procedures they’ve been taught to solve it.

It’s positive that upwards of 90% of Australian 15-year-olds tested in PISA 2022 wanted to do well in their maths classes.

It is also encouraging that the average Australian teacher of maths students in this age group was found to have high goals and views of teaching maths, irrespective of the socioeconomic background of their schools.

ACER has now produced 5 reports on Australia’s results from PISA 2022 on behalf of the Australian, state and territory governments. Collectively, they show the importance of the richness of the PISA data, including teacher and student voices, to our understanding of how to develop capable young adults.

Learn more

Read the full report: PISA 2022 A closer look at mathematics in Australia by Lisa De Bortoli and Catherine Underwood

See all of ACER’s reports on PISA 2022