Closing the gap of educators’ competence in early childhood education: Lessons learned from Southwest Sumba

Research 19 May 2022 8 minute readThe implementation of early childhood education can be viewed with at least two lenses: equitable access and quality of provision.

The first 1,000 days of life and the subsequent early childhood years have been considered an important window of opportunity in human development, and many have called it the golden years or golden age. The importance of early childhood is also acknowledged globally as early childhood development has been linked with at least 11 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which all UN Member States have adopted. To support early childhood development, the role of pre-primary education (Early Childhood Education or ECE) becomes one of the important aspects.

The implementation of ECE can be viewed with at least two lenses: equitable access and quality of provision. Research such as by the OECD and ADB in 2015 has shown that high-quality ECE brings numerous benefits for an individual, including health, less high-risk behaviour, and increased productivity, leading to higher future incomes. To ensure that equitable and quality ECE is provided, the Indonesian government has made endeavours by establishing the policies (One Village One Early Childhood Centre), laws (Education Law No. 20/2003), regulations (Presidential Regulation No. 60/2013), and guidelines to be implemented at the city and district levels. These documents also include standards to be adhered to, including aspects of the learning environment and teacher quality.

Indonesia has made noteworthy progress in terms of access as the ECE provision and participation rate grew steadily over the years. However, enrolment in ECE is of limited value unless it is of a sufficiently high standard. According to a World Bank report in 2020, in Indonesia, the quality of ECE varies widely across settings, and, on average, the quality is still low. Only a small percentage of nonformal ECE services are accredited, and although 80 per cent of rural ECE services have been reported to have met the national standards, not many have met the minimum quality standards in internationally validated metrics.

It is commonly accepted that skilled or competent teachers are crucial to quality ECE. Indeed, the government has decreed the qualification standards for ECE educators (i.e. ECE teachers, ECE teacher assistants, and caregivers). ECE teachers must hold a bachelor’s degree in ECE or Psychology, teacher assistants in nonformal ECE centres must have postsecondary training in ECD, and caregivers in nonformal centres must be secondary education graduates or similar level.

The difference in required qualifications for different types of ECE educators may explain the findings from an ACER study conducted in 2017 commissioned by the Analytical and Capacity Development Partnership (ACDP 033). The study found that early childhood educators vary in their academic qualifications and, potentially, in their competence. In 2015/2016, 49% of kindergarten teachers were qualified with a bachelor’s degree compared to 24% of non-kindergarten teachers. A more recent finding from a World Bank report shows that by 2019/2020, there was a more significant percentage of teachers in kindergartens (69%) with at least a college education compared with those in nonformal ECE centres (35%), which perhaps can be explained by the differing qualification requirements. Among nonformal ECE teachers, the majority (60%) were senior secondary education graduates or lower, and only 5% had a postsecondary diploma.

There are opportunities for professional development for ECE educators to close the gap in teacher qualification and potentially in teacher competence. Block grants can be used by ECD teacher associations and private education institutions to conduct teacher training. The government also has established a certified and tiered training program for ECE educators, including those with secondary education degrees, aptly named Diklat Berjenjang (lit. tiered training). The three-tier training program allows ECE educators to upgrade their qualifications and improve their understanding and skills to provide quality teaching. However, professional development is not mandatory, and because of capacity and financial constraints, these programs may not be available to educators across Indonesia.

Lessons Learned from Southwest Sumba

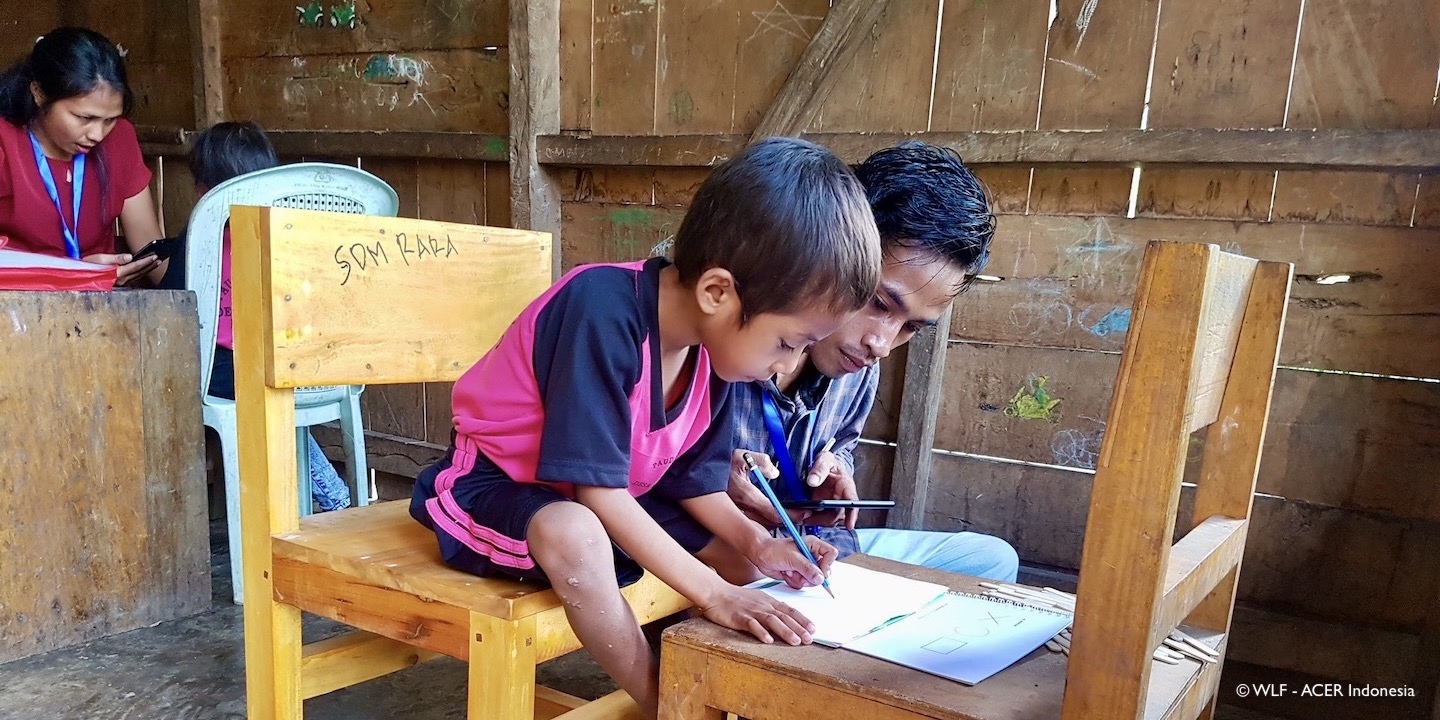

In 2020, partnering with the William & Lily Foundation and Adaro Bangun Negeri Foundation, ACER studied the quality of early childhood development provision, including capacity building for ECE educators, in 12 villages in Southwest Sumba Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province. The regency was selected as the study’s focus because of the relatively low human development index (62.60 out of 100 in 2019). Enrolment of children aged 5-6 years old in ECE was considered relatively low (67% in 2018). There are many hard-to-reach rural areas, making equal provision of any basic service difficult. The area also has a unique culture or way of living that is different from the culture on the main islands (e.g. Java or Sumatera), thus requiring a different approach to policy and program implementation.

Indeed, the study found that there was limited provision or supply of structured training programs such as Diklat Berjenjang. It may be caused by the lack of eligible organisations to produce the certificates and the insufficient public funding, as ECE is not considered a compulsory part of the national education system, especially in districts where public funding is limited. Most professional development activities were ad-hoc self-initiated peer group discussions, peer coaching, or self-study.

From the demand side, ECE educators reported finding that structured training programs are expensive and hard to access. The geographical challenge in Southwest Sumba may contribute to this, as ECE educators struggle to get to the training venue, which drives overall costs in transportation and time taken away from families and other economic activities – many ECE educators also farm. They also claimed that they lacked the pre-requisite to participate and that the programs did not meet their requirements. Many ECE educators stated that the reason was that they had a low degree of education. The available training programs also had not incorporated group discussions and materials to take home and lacked regular mentoring or coaching. They were considered important aspects of teacher training by the ECE educators.

The 2020 study was followed by quasi-experimental research the following year (2021). These ECE educators were provided with Diklat Berjenjang training, which incorporated group discussions, materials to take home, and follow up coaching. Although it is still too early to present the results and formulate recommendations from this follow-up study, the hypothesis that is now forming is that there is a need to cater the design of the tiered training, including the content and delivery, to the needs of ECE educators in Southwest Sumba. It is worthy to also consider the limitation of this study, which is the study being conducted in selected areas where there was no previous interventions and high stunting rates. However, the initial hypothesis is in line with UNICEF’s principles guiding the elements of quality ECE, in which the design of ECE must take local contexts, cultures and needs into account – including those of ECE educators.

There are examples from other areas in adapting national programs into local settings, such as the mother tongue-based multilingual education approach, which has been piloted in Papua, where the mother tongue language is used as the language of instruction. Examples can also be taken from countries with multicultural societies in which culturally responsive practices are growing, such as Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, which have started equipping teachers and academic staff with competence in cultural sensitivity. As there are differences in contexts and settings between Southwest Sumba and these other areas, the study will also be careful in adopting the approach.

However, what most important is to find the key component needed to ensure the successful adaptation of nationally designed training into local settings and one that is responsive to the needs of local ECE educators, particularly those in rural and remote areas with unique cultural settings and limited access to a formal academic qualification. With successful adaptation, it may reduce (if not close) the gap between educators’ qualifications and potential competence and improve the quality of ECE provision in the long run.