Three science concepts primary students struggle to grasp

ACER news 11 Aug 2023 4 minute readA new global study by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) has identified 3 fundamental concepts that have continued to elude Year 3 students for decades.

Dr Kristy Osborne, a physicist, former pre-service teacher educator and research fellow with ACER, examined the scientific knowledge of more than 8,000 Year 3 students for her research paper ‘Difficult physical science concepts in middle primary’.

Published in the journal, Teaching Science, it identifies volume and mass of gases, mass in relation to size, and the earth-sun-moon system as areas attracting misconceptions that are ‘highly resistant to change and typically pervade students’ views across countries and cultures’.

The paper aims to improve children’s scientific knowledge by identifying points for teachers to focus on in progressing learning and embedding the understanding of difficult concepts in student thinking.

The research draws on the responses of Year 3 students to the International Benchmark Test (IBT) that ACER conducts regularly in 18 countries.

Reviewing 4 testing periods between 2013 and 2018, Dr Osborne analysed how children responded to 40 questions covering different scientific knowledge and skills.

Overall, the research found:

- 27% of 8,433 students believed bigger objects always have more mass than smaller objects (see experiments 1 and 2 below),

- 74% of 2,042 students believed air has no mass and/or volume (see experiment 3), and

- 36% of 808 students believed day and night is the result of the earth orbiting the sun.

Dr Osborne also reviewed 30 years of relevant international research to confirm these misconceptions have persisted over time.

‘These findings would indicate that there has been little change in the number of students holding these alternate conceptions over the last 30 years,’ Dr Osborne says.

The experiments and how children responded

The research identified 3 questions about hypothetical experiments where a significant number of children chose a wrong answer from the choices offered in the IBT tests.

Experiment 1 involved melting and cooling 4 blocks and then shaping them into one new block. Children were asked to compare the weight of the new block with that of the 4 smaller ones and choose from 4 alternative answers.

Between 25% and 29% of 8,433 students over the 4 testing periods answered that the new block would weigh more than the 4 small blocks.

Experiment 2 (included in 3 testing periods) arranged the 4 blocks in different formations, with between 20% and 28% of 6,402 students choosing the misconception that blocks stacked on top of each other would weigh the most.

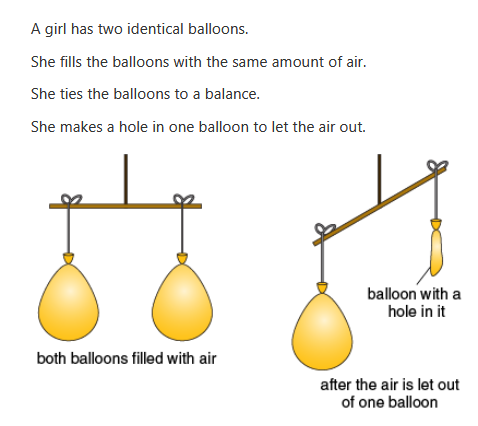

Experiment 3 (included in 2 testing periods) focused on gases. One of two inflated balloons hanging from each end of a balancing rod was popped, resulting in the remaining inflated balloon dropping to a level below the deflated one.

When students were asked what the experiment showed,74% chose the response that air has no mass and/or volume – a similar result to that found in research from 1991.

‘Combining our results with [results from the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Project 2061] and noting that alternative conceptions often traverse culture and language, it would appear that the alternative conception – air has no mass – emerges in the early primary years and remains throughout the entirety of students’ schooling,’ Dr Osborne concludes.

A fourth question was confusing even for high-performing students, the research notes. It asked what caused the earth to have day and night, with 36% choosing the right concept (earth spinning on its axis) and 36% choosing the misconception (earth orbiting the sun).

Why it’s important to dispel alternate beliefs early

‘One barrier to achieving scientific literacy is strongly held beliefs … that are not grounded in scientific fact,’ Dr Osborne says.

These can be established before children come to the classroom, based on a seeing-is-believing understanding of the world, everyday experiences and reasoning, making them difficult to shift.

Dr Osborne recommends that Year 3 teachers assess whether their students hold any of the misconceptions identified by the research and use the predict-observe-explain model ‘to highlight the inconsistency between reality and the tightly held alternative conception’.

The full paper - Difficult physical science concepts in middle primary - has been published in the Teaching Science Journal.